Signs of a Delusional Mind

These are the chronicles of the esoteric . . .

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2012

any other name: a disclaimer

William Shakespeare, in his play Romeo and Juliet, famously suggested that a name has no bearing on the essence of a thing. The herione argues that Romeo would be who he is whether he had the name Montague or not - for a foot constitutes a Montague as much as a hand or a face or an arm. His name means nothing, and so it should be least of all what keeps the two love-struck teens apart. 'What's in a name?' she asks. 'That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.'

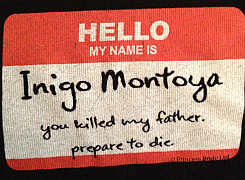

From a t-shirt my sister gave me.

© Princess Bride Ltd.

What's in a name indeed.

For many ancient (and perhaps many current) cultures, words and names have much more power than we here in North America give them credit. We all know this to be true on some level; the old adage 'sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me' has always proven to be false. Throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, the language of blessings and curses is so important because uttering a positive word or an ill one was as good as guaranteeing the recipient to experience good or bad. Being aware of this concept clarifies Jacob's betraying action before his father, Isaac. Once the word of blessing - meant for his elder brother Esau - was spoken upon Jacob, it could not be revoked.1 The blessing was given, verbally released to be enacted, and there was nothing Isaac or Esau could do about it.

Likewise, for many cultures a name is seen to hold power and significance. Many Aboriginals are given private and personal spiritual names. To know someone's name gives you a level of power over them: You say their name and they will respond. Furthermore, the name of a thing is its representation and in many ways conveys its nature and essence. In the Scriptures, key figures are given names that either foreshadow what sort of person they'll be (i.e., Jacob), or are are re-named according to a life-changing event to signify the 're-birth' (i.e., Abram/Abraham, or Jacob/Israel). We understand this concept to some degree when we speak of BMW being a good name in the car business or in the emotions evoked by the mention of Hitler. A name in fact represents a history and reputation.

It is for this reason the ancient Hebrews and modern Jews show such reverence for Adonai that they use alternative ways to address Him in order to avoid speaking His holy Name with unclean lips - since a name represents what is named, the name itself is understood to be treated with the same amount of respect as the object itself. Traditionally, it was only the High Priest who could speak Adonai's Name and then only in the Temple on Yom Kippur. Such deliberate veneration goes especially noticed in the written word, where Jews avoid even writing 'God' in the full, opting instead for 'G-d' and thus preventing any possible defacing of His Name. Accordingly, every Jewish website includes a disclaimer for anyone who prints an article from them warning that a page with any name of Adonai is to be treated with appropriate care.

As many of you may have noticed, I've attempted to adopt this practise throughout my blog as much as possible. I appreciate the sense of mystery, wonder and awe that Jews invest in the Holy One - something that seems deficient in many Christian circles. I have chosen to use a number of substitions to address our God for various reasons. Firstly, I am attempting to avoid the assumptions - negative or otherwise - surrounding the use of 'God' prevalent in our culture. Secondly, I am reaching back to our Jewish roots, attempting to re-infuse a Jewish ambience and structure into Christian theology, and in this way point to the specific God of the Israelites.

I would like to explain some of them for you.

The Name Adonai is traditionally used in prayers, and when reading Scripture it is used as a substitute for what is known as The Holy Tetragrammaton.2 The Tetragrammaton - also known as The Sacred Name - is the most common Name for God used throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, therefore placing Adonai among the most commonly used Names as well. The Sacred Name is spelled YHWH and is pronounced by simply saying the Hebrew letters yod-hei-vav-hei.3 This is the Name given to Moses from the burning bush and can be translated in a number of ways, all of which are variations of 'I Am Who I Am,' 'I Am the One Who Is,' or 'I Will Be What I Will Be.' Adonai is typically translated as 'Lord,' and literally means 'my master/my lord.'

I have also often used Elohim - another very common Name used in Scripture occuring 2 570 times. This Name is the plural of the Hebrew el, which means 'strong one' and is used in other Semitic languages in reference to a god. Elohim however is unique to Hebrew, not found in the other related languages and throughout Scriptures is used with singular verbs, adverbs and pronouns despite its plural ending. It is usually translated as 'God,' and is in fact the first Name given in Scriptures, as the Hebrew reading of Genesis 1:1 would be, 'In the beginning Elohim created the heavens and the earth.' Relatedly, I have also used Eloheinu, which simply tranlsates as 'our God.' My use of this Name is the clearest indication of my siding with the God of Israel, as opposed to any 'God' concocted from Greek and North American misunderstandings.

It is also necessary to address the fact that I have deliberately refused to use the term 'Old Testament' in my writing, choosing instead to simply write 'the Hebrew Scriptures.' I disagree with the attitude created - whether conscious or not - of a dichotomic Bible. To employ the language of 'old' and 'new' implies a division between the two sets of literature that is completely unnecessary and false. These concepts can be traced back to figures such as Marcion of Sinope who, around the year 140, compiled a collection of uniquely 'Christian' writings and completely rejected the theology and God depicted in the Hebrew Scriptures. He believed that the 'God of Jesus' was not noly different from but also superior to the 'God of the Israelites.'4 Similarly, around 170CE, Melito of Sardis compiled a collection of books he called the Old Testament. He believed the teachings found within this collection created a mold that was later broken by 'the truth' found in the New Covenant.

These things seem strange to us, but they are sadly not that foreign. Actions as small as handing out Gospels to new believers without the context of the Hebrew Scriptures show what part of the Bible we think is most important and which part we feel is disposable. The great Martin Luther of the Reformation (falsely) taught us that the theology of the Jews was out-dated and was to be replaced by the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. But to throw the first part of our Scriptures aside as secondary is a blatant disregard of centuries of history and divine interaction. Jesus never came to abolish the Law, but instead to fulfil it - to embody the Law in full and thereby show us what it means to truly live by it. If Jesus can be accused of changing the Law, it would only be for making it more strict, more difficult - and simultaneously more accessible.

To Jews, the Scriptures are known as the Tanakh,5 which is an acronym for the Hebrew names of the three categories the canon is divided into: Torah ('Teaching'), Nevi'im ('Prophets'), and Ketuvim ('Writings'). I'd like to come up with an equivalent for the canon of Christian Scriptures that is more neutral than 'new,' but as of right now I'm still working on a name.

1. Genesis 27:1-40.

2. In conversation, Jews will refer to Adonai as HaShem, which is literally translated as 'The Name,' and will do so even when speaking English.

3. It has become commonplace for Christian scholars to use Yahweh as the Sacred Name. This is wrong on two levels. In the first, Christians throw the Name around far too flippantly. In the second, the addition of the vowels is a misreading of the Masoretic texts. The Masoretes are famous for adding vowel punctuations to the otherwise consonant-only writings of Hebrew. However, it is believed that the vowels added to YHWH in the Scriptures were in fact merely the vowels of Adonai placed there as a reminder to not speak the Sacred Name, but instead to use its substitute.

4. While Marcion was excommunicated as a heretic, his work forced early Jesus-followers to examine what documents they considered authoritatve and therefore to compile a canon of Christian Scriptures (which ultimately differed from that of Marcion's).

5. The Scriptures are also known as the Miqra, translated as 'that which is read.'

Subscribe!

Subscribe! Contact me!

Contact me!